Early last year, as the novel coronavirus spread across the United States, so, too, did racist, xenophobic narratives blaming Asian people for the pandemic.

Prejudice against Asian Americans and other communities of color did not arrive in the United States with the first case of COVID-19. But rhetoric attributing the pandemic to people of Asian descent fueled a rise in discrimination and violence.

President Donald Trump was quick to blame China for the pandemic and repeatedly referred to COVID-19 as “the China Virus” and “kung flu.” A recent study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that after President Trump tweeted the phrase “Chinese virus” in mid-March of last year, the number of anti-Asian hashtags on Twitter soared.

But the narrative did not stem from the White House alone.

In April 2020, the National Republican Senatorial Committee distributed a 57-page memo to Republican candidates, advising them to address the coronavirus by attacking China. It stressed three key talking points: that “China caused this pandemic by covering it up, lying, and hoarding the world’s supply of medical equipment”; that Democrats are “soft on China”; and that Republicans will “stand up to China… and push for sanctions on China for its role in spreading this pandemic.” The authors of the memo were not blind to possible repercussions of this messaging: The memo lists “Aren’t you being racist by blaming China and causing racist attacks against Chinese Americans?” as a “likely argument” for which candidates should prepare responses.

According to The Denver Post, numerous Colorado Republicans “ramped up” criticism of China in the weeks following the memo’s publication. And in September 2020, when U.S. Representative Grace Meng (D-NY) introduced a resolution condemning COVID-19-related anti-Asian sentiment, 164 legislators, all members of the Republican Party, voted in opposition. Representatives from Colorado voted along party lines.

Insinuations that China is singularly responsible for the pandemic have also circulated in the mainstream media, such as op-eds in the Washington Post titled “China should be legally liable for the pandemic damage it has done” and “The coronavirus has helped us finally see China for what it is.” Major media outlets have also repeatedly published photos of Asian people alongside unrelated coverage of COVID-19. When the New York Times reported on the first case in New York — a Manhattan resident who had recently traveled to Iran — the story was accompanied by a photo of pedestrians in Flushing, a predominantly Asian neighborhood in Queens.

The pervasive narrative that people of Asian descent are more likely vectors of disease or are otherwise responsible for the spread of COVID-19 has no scientific basis. It also actively fueled discrimination and violence against Asian Americans.

A Rise in Anti-Asian Violence

Asian Americans have faced heightened discrimination and violence since the onset of the pandemic. In February 2020, even before COVID-19 reached Colorado, local Chinese restaurants reported a 30-40% drop in business due to racist stigma around the virus. In Littleton, a Thai restaurant was vandalized with a hate symbol. Across the state, Asian American Coloradans have reported being spit on, pushed into oncoming traffic, verbally harassed, and threatened.

Throughout the nation, Asian Americans have also been targeted in a wave of physical attacks. A family with a 2-year-old baby, an Air Force Veteran, and a high school teacher are among those who have been severely harmed simply for being Asian while doing everyday things like waiting for the bus, going for a walk, or grocery shopping. And the violence has spanned all ages, from elders, including a 91-year-old being shoved to the ground in Oakland, to young people, including a 13-year-old playing basketball.

These assaults are horrendous, and they are only a fraction of the hate that the Asian American community is facing.

Hate Crimes Against Asian Americans

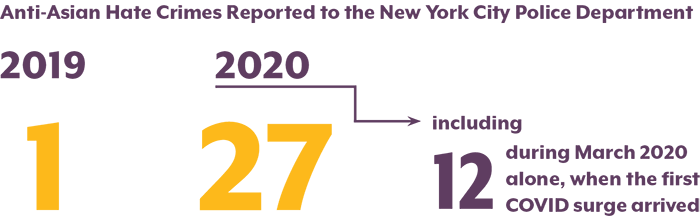

At the federal level, a hate crime is defined as a crime — often violent — that is motivated by bias against an individual's race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, or disability. As a result of the dangerous and racist rhetoric used to describe COVID-19, there was a rise in the number of anti-Asian hate crimes reported to the police in 2020. The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism (CSHE) reports that in 16 major cities across the U.S., hate crimes overall decreased by 7%, but anti-Asian hate crimes increased by almost 150%.

The New York Police Department Hate Crimes Dashboard shows the number of confirmed hate crime incidents per month by type of bias. The data are telling: In 2019, one anti-Asian hate crime was confirmed in New York. In 2020, 27 were confirmed, with almost half occurring in March alone. Xenophobic Google search terms and Twitter posts also spiked in this month, according to CHSE data.