Culturally Responsive Care, Discrimination, and Language

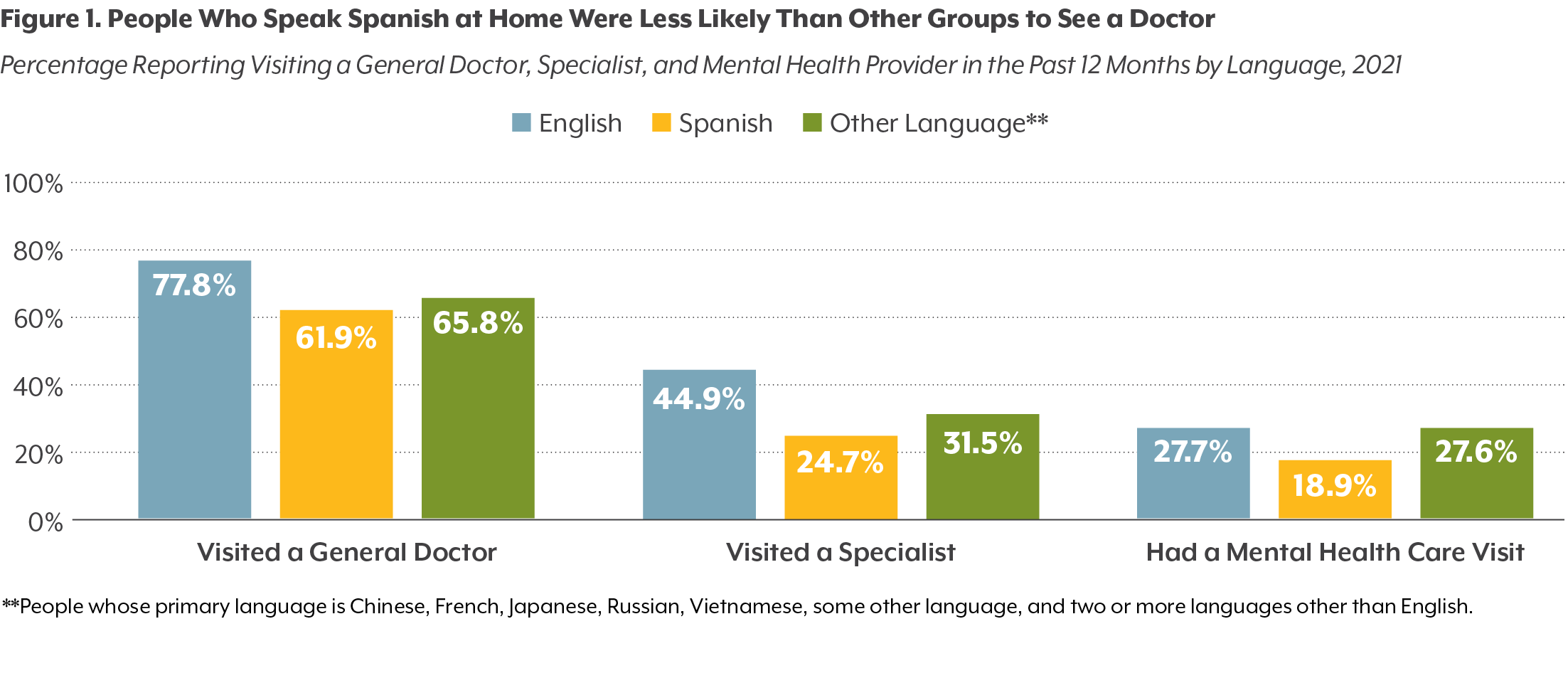

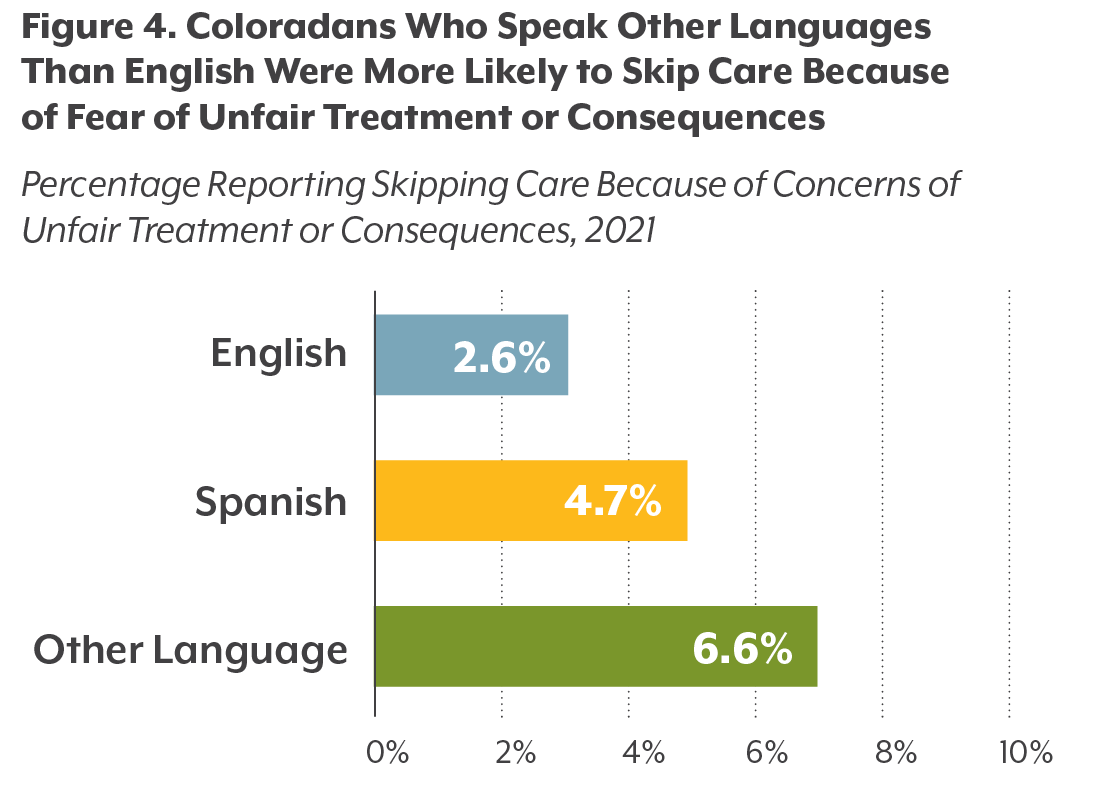

People who spoke a language other than English at home were about twice as likely as English speakers (6.6%, compared with 3.2%) to feel like they were treated with less respect or received services that were not as good as what other people get when engaging with the health care system, according to the CHAS.

Discrimination when seeking health care services can lead to increased stress, medical noncompliance, lower patient engagement, and avoidance of health care services, all of which contribute to the prevalence of poor health outcomes among disproportionately affected groups. This points to a need for culturally responsive care — the ability of health care providers and systems to deliver care that meets the social, cultural, and linguistic needs of patients that they serve.

Coloradans also report a need for culturally and linguistically responsive care: About 7% of Coloradans reported that they needed health care that was responsive to specific characteristics, including race, gender identity, sexual orientation, a disability, and language, among others. Of these Coloradans, about one in four (24.3%) identified their language as a characteristic that made a difference in the kind of care that they needed.

Language, Health Care, and Policy

Access to care that is culturally responsive is important in reducing poor health outcomes. Policies at the federal and state level — and programs within health systems and schools — can make a difference.

The 1964 Title VI Civil Rights Act and the Department of Health and Human Services identify failure to provide access to language interpretation in hospitals that receive federal funding as discrimination. Additional safeguards under the Affordable Care Act protected the right of patients with LEP to have access to interpretation and translation services, but the Trump Administration removed some of these protections in 2020. One example of the removed provisions was the requirement for resources called taglines for those receiving federal dollars. Tagline provisions – small sentences that were posted in the top 15 language groups about availability of language assistances services – were previously required on website content and documents used to obtain health insurance coverage or access health care coverage.

While these protections are no longer mandated at the federal level, Colorado policymakers have continued to push for improved language access. The 2021 Colorado Standardized Health Benefit Plan Act, also known as the Colorado Option, aims to reduce health care disparities among diverse communities with provisions focusing specifically on language access. For instance, the act requires culturally responsive health care networks whose providers reflect the diversity of their enrollees.

To date, Colorado policies have emphasized ensuring written translation of health information for LEP patients. These policies leave the option of obtaining interpreters (dealing with language in real time) up to providers. From one hospital or clinic to another, interpretation services vary from 24/7 telephone services to in-person staff to video-calling, where it can take anywhere from 10 minutes to 72 hours to be paired with the right interpreter depending on the service used.

Lack of standardization of interpreter expectations and service types can lead to issues such as family members, often children, inappropriately being used as interpreters; patients being matched with an interpreter of the wrong dialect; or patients being turned away due to the inability to find the correct interpreter. A goal of the Colorado Option is to better standardize expectations of interpreter services.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only highlighted how crucial it is for patients and providers to be able to communicate. Telephone interpretation is difficult while wearing full personal protective equipment or when standing six feet away. Not having time to find an interpreter when a patient is in critical condition can be the difference between life and death.

Health systems and medical training programs can play a role in changing these dynamics. Integrating culturally responsive learning into training curriculum can help provide the workforce with tools to meet the needs of patients. Programs and providers can take steps to increase the linguistic diversity.

Conclusion

The many languages spoken by Colorado’s residents contribute to the richness and diversity of the state. Making sure health systems reflect this diversity is of utmost importance.

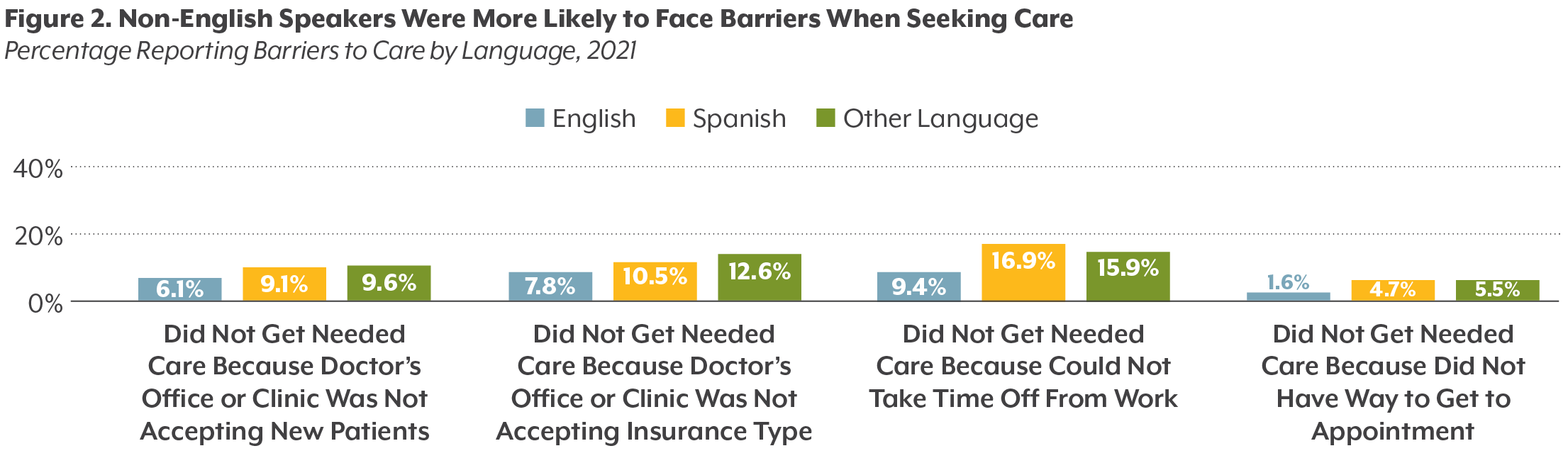

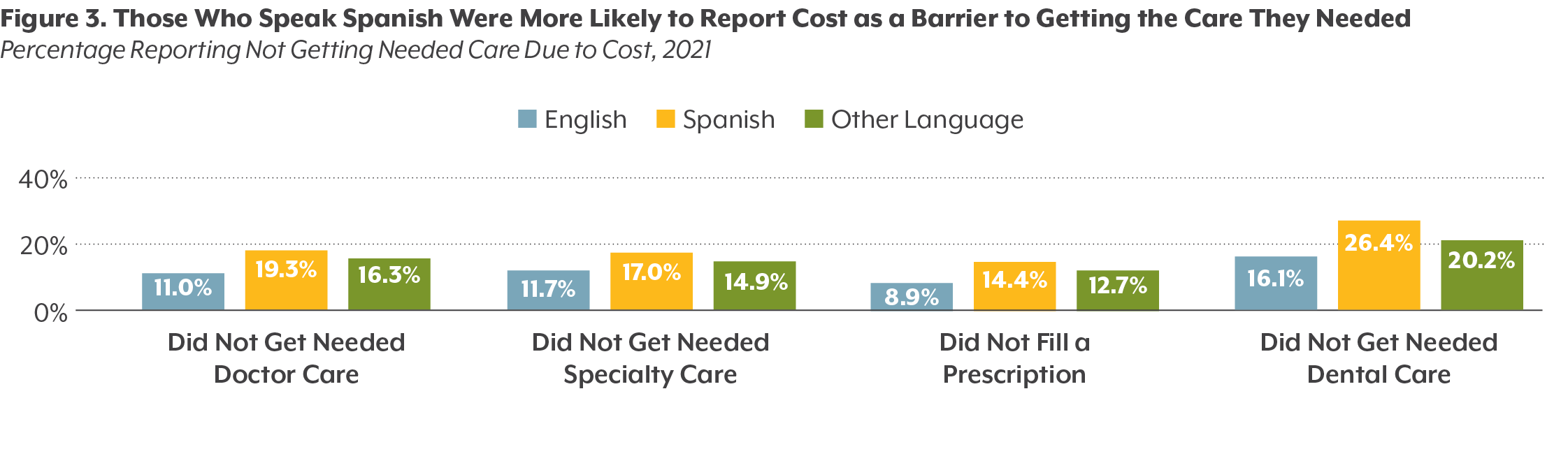

Coloradans who speak a language other than English at home experience the intersection of barriers to seeking care and were more likely to experience financial stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic. Access to culturally responsive care and the reduction of harmful health care experiences due to discrimination are integral in increasing the use of care and quality of care experienced by Coloradans.

Access to translation and interpretation services within the health system is of utmost importance. Establishing culturally responsive and diverse health care networks and creating uniform policies to protect patients’ rights are some ways to help reduce barriers experienced by different language groups across our state.

Aya Ahmad contributed as a co-author of this report.