An old idea is back on the table as Colorado policymakers search for ways to control Medicaid costs.

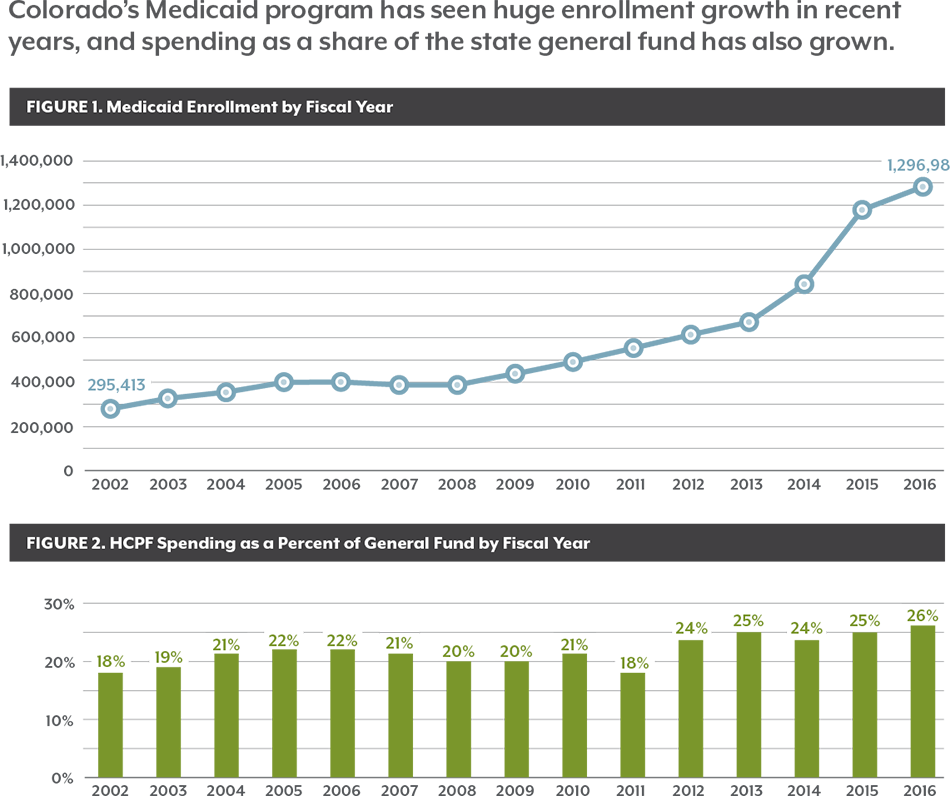

Enrollment in Health First Colorado, the state’s Medicaid program, has grown rapidly, and the state’s costs have grown, too. More than 1.3 million Coloradans are covered by Medicaid, and the shared federal-state program now accounts for 26 percent of the state General Fund, up from 18 percent in fiscal year 2001-2002.

The program’s growth has policymakers searching for ways to control costs without cutting services for Coloradans who depend on Medicaid for access to health care.

One idea is Medicaid managed care. It’s an idea that Colorado has tried in the past and largely abandoned.

However, most states have turned to Medicaid managed care to get their costs under control — with varying levels of success. Colorado still has a handful of programs that use elements of managed care.

In a managed care system, the state Medicaid agency contracts with managed care organizations (MCOs) — usually private insurance companies that work with providers to serve Medicaid patients. MCOs bear the financial risk if spending is higher than expected but also have the potential to reap financial rewards if they control costs. As a concept, Medicaid managed care appears straightforward, but there are numerous nuances and variations to its implementation, and it isn’t always clearly understood. In this paper, the Colorado Health Institute (CHI) examines the three elements of a managed care system:

- Contracted agreements with managed care organizations;

- The use of a medical home, a health care provider whose goal is to improve the coordination of care to enhance quality and reduce unnecessary costs;

- Capitated payments, which allot a specific amount of money to a MCO for every patient. The insurer is then responsible for covering all health care needs, regardless of cost. This means the insurer bears the financial risk when care exceeds the capitated payment amount.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the federal agency overseeing Medicaid, highlights the promise of this approach, saying it could allow states to “reduce Medicaid program costs and better manage utilization of health services.”1

Managed care also offers legislators the promise of greater certainty over the annual Medicaid budget. Once the payment rate is set in the contract, any change in spending becomes the responsibility of the MCO.

But is managed care really the cure-all for Medicaid some claim it to be?

Colorado experimented with managed care in the 1990s — unsuccessfully. Payment disputes between the state and MCOs spurred lawsuits, and Colorado ended its managed care program.

But past failure does not mean another try would be doomed. Much has changed over the years. Health systems have a lot more data to make better decisions, and policymakers have the benefit of seeing what has and has not worked in different programs in Colorado and in other states.

Colorado has the option to stay the current course, which offers more familiarity and less disruption or adopt a full managed care model, which would be riskier but may — or may not — bring greater savings and more budgetary certainty in the long run.

The state’s Medicaid program has already successfully leveraged many managed care techniques, and CHI is exploring whether an even bigger bet on Medicaid managed care could work in Colorado. This introductory report examines the elements of managed care and initiatives in Colorado Medicaid that draw upon managed care principles. Future reports will look at other states’ experiences with Medicaid managed care and quantify the potential risks and rewards of a new approach.

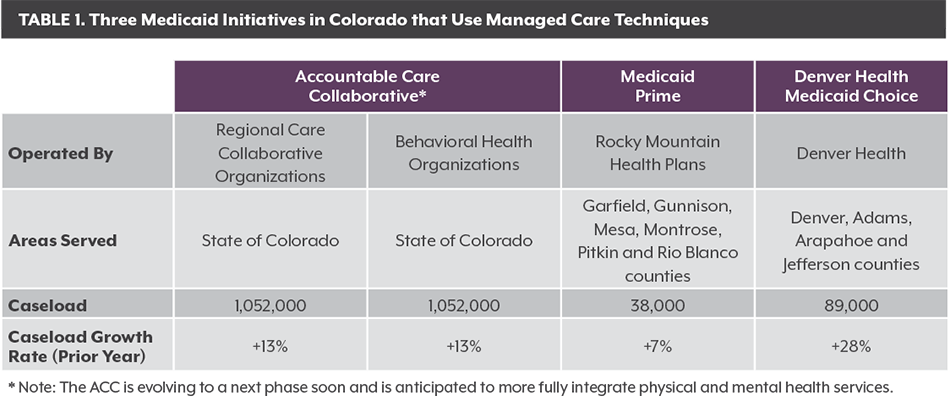

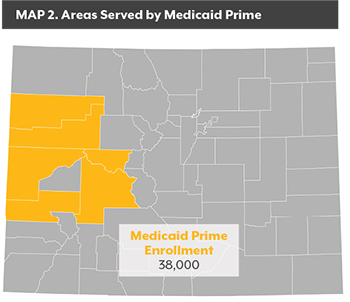

RMHP receives a PMPM payment from the state to cover the medical needs of those enrolled in Medicaid Prime. RMHP in turn makes capitated payments to primary care providers, who serve as medical homes for their patients. RMHP also is responsible for paying for other services such as hospital and specialty care, though those payments are based on a FFS approach. Medicaid Prime does not cover mental health services, though RMHP works with mental health centers to enhance the integration of physical and mental health services.

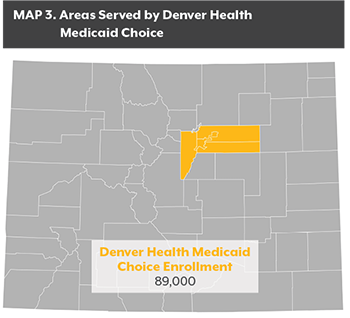

RMHP receives a PMPM payment from the state to cover the medical needs of those enrolled in Medicaid Prime. RMHP in turn makes capitated payments to primary care providers, who serve as medical homes for their patients. RMHP also is responsible for paying for other services such as hospital and specialty care, though those payments are based on a FFS approach. Medicaid Prime does not cover mental health services, though RMHP works with mental health centers to enhance the integration of physical and mental health services. Launched in 2004 by Denver Health, a comprehensive care safety net organization, it now covers about 89,000 enrollees in Denver, Adams, Arapahoe and Jefferson counties.4

Launched in 2004 by Denver Health, a comprehensive care safety net organization, it now covers about 89,000 enrollees in Denver, Adams, Arapahoe and Jefferson counties.4