A New Day for Mental Health Coverage?

The lasting legacy of the great thinker Rene Descartes – that the body and mind are separate - has created some complicated downstream consequences for mental health care.

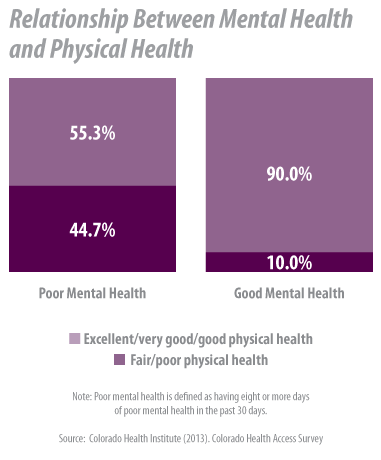

The data show that physical and mental health are related. Happier people are healthier people. But the body and mind have been treated as separate entities for so long that two different systems of care and insurance coverage evolved.

New federal regulations related to mental health parity are aimed at addressing the problem.

The federal government on November 8 released the highly-anticipated final regulations for the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA). The new rules are designed to help achieve the parity mentioned in the title by requiring that insurers provide substance abuse and mental health treatment benefits that are no more restrictive than their medical and surgical care benefits. (Note that the rules apply only to those insurers who choose to offer substance abuse and mental health treatment benefits.)

So what is parity, anyway? The law defines it broadly, including elements such as insurance cost-sharing; limits on use of treatment services; use of care management tools; and the criteria for determining what care is medically necessary.

The final regulations are a response to comments and questions about the interim regulations that came out in February 2010. For example, the final rules ensure that parity applies to intermediate levels of care, such as residential treatment or intensive outpatient care. Also, the rules apply to all geographic limits and network adequacy standards.

Parity has been an ongoing process at both the federal and state level.

Although the mental health parity law does not require insurers to cover mental health or substance abuse treatment, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) does. This is part of the essential health benefits that must be included in insurance sold to individuals or small groups with 50 or fewer employees starting in 2014. The ACA requires that these plans also comply with the mental health parity law.

States can require more of health insurance plans than what is federally mandated. Colorado has required some insurance plans to cover a selection of mental health services and treatment for alcoholism since 1976.

The state introduced mental health parity in 2008, and last year passed a law that aligns Colorado law with federal law, requiring that individual group plans, small group plans, and large group plans for those with 50 or more employees cover mental health and substance abuse treatment. This coverage must be “no less extensive than the coverage provided for physical illness.”

Some insurance plans are not subject to Colorado law, including self-funded plans in which an employer assumes direct financial responsibility for claims. These self-funded plans are regulated by the federal government, and while the mental health parity law does apply to them, they may choose to opt out. Medicare and fee-for-service Medicaid plans are not required to comply with the mental health parity law.

OK. But what does all of this actually mean for consumers? For people covered by most private insurance plans, the law means that:

- If you make a 30 percent coinsurance payment for inpatient medical services, your coinsurance rate for inpatient mental health services can’t be higher than 30 percent.

- If there is a 20-visit cap on visits to a physician for physical illness, the cap on visits to a physician for mental illness must be no less than 20 visits.

- If you pay 100 percent for medical services out of your network, you will likely have to pay 100 percent of mental health services out of your network.

The 2013 Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS) found that nearly eight percent of Coloradans, or about 377,000 people, needed mental health services in the past year but did not get them. The most frequently reported reasons for this were related to cost – being uninsured, being worried about what insurance would cover, and general concern about the cost of treatment.

While parity rules may remove cost barriers for many, it does not ensure that people will seek the services they need. Mental health has historically been taboo (think Mad Men or the Sopranos), and that persists. Among Coloradans who did not get needed mental health services in the past year, the CHAS reported that 31 percent cited not being comfortable talking about personal problems with a health professional as a contributing factor.

If the parity rules begin to chip away at cost barriers, it will be interesting to see if fewer people report not getting needed mental health services, and if increased use helps decrease the stigma.

Requiring that mental health and substance abuse services be covered in parity with medical health services is part of a larger effort to recognize that behavioral health and physical health are connected. Efforts to integrate behavioral health and primary care are ongoing across the state, and the Colorado legislature has significantly increased state spending on mental health.

Together, all these efforts could represent a new day for mental illness and mental health services in our society.