It’s the Prices, Stupid . . . Or Is It?

The high cost of health care is a big concern for people in Colorado’s mountain counties and on the Western Slope. At CHI’s Hot Issues in Health conference in December, several county commissioners and legislators from those areas told me that health care costs are a top priority.

So why is it so expensive to get health care in these parts of the state?

To economists, this is a question of whether “P” is the main culprit or whether “Q” is the main culprit. “P” is the price of health care services used while “Q” is the quantity of health care services used. Spending on health care services reflects both.

A recent New York Times article points out that many economic studies pin the blame on prices.

Uwe Reinhardt, the highly regarded Princeton health economist who passed away last November, made this point bluntly in a 2003 study titled “It’s the prices, stupid.” He showed that health care spending per person was more than twice as high in the U.S. than in other developed countries, even though the U.S. did not use a higher quantity of health care services. Ruling out quantity meant that high U.S. spending was mostly due to higher prices for health services, he concluded.

Similarly, a recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that factors such as population growth, a greater proportion of seniors and changes in disease levels all affect the quantity of health services that are consumed. Still, those factors explain only a modest portion of the increase in U.S. health care spending from $1.2 trillion in 1996 to $2.1 trillion in 2013 (adjusted for inflation). The JAMA study argued that increasing prices were a major factor in the rise in spending.

The idea that higher and higher prices are driving the climb in health care spending conjures up images of villainous insurance carriers and health care providers taking advantage of consumers by jacking up prices.

But the story is not at all clear. Nor is it clear that the correct policy response should focus exclusively —or even primarily — on prices.

Evidence, including some from Colorado, indicates that the other part of the spending equation — the quantity of health care services — deserves more attention. One study notes that Medicare spending in the U.S. varies substantially by geography, and that differences in the quantity of health care services are the major explanation. This study argues that strategies to address health care spending need to target both the price and quantity components.

Recent Colorado data point to quantity as the main explanation for high health care spending on the Western Slope.

Spending for outpatient services on the Western Slope’s insurance region — basically the western half of Colorado, excluding the Grand Junction area — is about 87 percent higher than the state average, according to analyses by the state’s Division of Insurance and the Colorado Commission on Affordable Health Care. This also appears to contradict the “It’s the prices, stupid” idea.

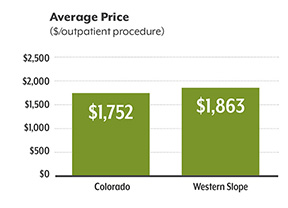

First, a look at the “P”: The average price per outpatient procedure is $1,863 on the Western Slope, only about six percent higher than the state average of $1,752. (See the graph with the green bars.)

First, a look at the “P”: The average price per outpatient procedure is $1,863 on the Western Slope, only about six percent higher than the state average of $1,752. (See the graph with the green bars.)

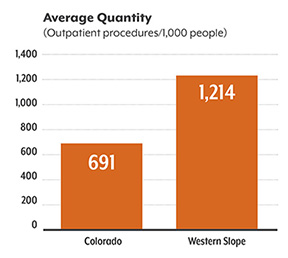

But next, a look at the “Q”: The Western Slope has an average of 1,214 outpatient procedures per 1,000 residents — about 76 percent more than the state average of 691 outpatient procedures per 1,000 residents. (See the graph with the orange bars.)

Clearly, the big difference is quantity. What’s driving the higher quantities of health care services on the Western Slope?

Well, the explanation might not be anything nefarious. The quantity of health care services provided is the result of everyday decisions made by patients and providers. The decision to perform more procedures might reflect a desire to make sure the patient is as healthy as possible. (Of course, one can also imagine that the higher quantity could be tied to providers trying to maximize their profits, but that’s a topic for another day.)

But high rates of health care usage also can reflect the misuse of resources that don’t improve health. More isn’t always better.

But high rates of health care usage also can reflect the misuse of resources that don’t improve health. More isn’t always better.

One intriguing initiative to turn this idea into action is called Choosing Wisely. Spearheaded by the American Board of Internal Medicine, this program encourages providers and patients alike to understand and engage in conversations about using evidence-based tools to avoid wasteful or unnecessary medical tests. In addition, the Colorado Commission on Affordable Health Care recommended that the state support voluntary opportunities for providers to examine data on health care usage “to identify areas of utilization that can be addressed to reduce health care spending.”

Even though we don’t know for a fact that the high usage rates in certain parts of Colorado reflect wasteful spending, I think there is enough suggestive evidence for us to think a lot more seriously about examining the quantity aspect of Colorado’s health care spending.

Reducing the quantity of health care services will be a challenge. Decisions about which medical tests or procedures to conduct involve clinical judgment. Legislators and regulators will be hard pressed to effectively guide, manage or mandate those clinical decisions.

I think much of the responsibility will rest on providers to take a hard look at health care usage — in a collaborative, not adversarial, manner — and find ways to address to these concerns. We all have a stake in the success of such efforts.

Find CHI on Facebook and Twitter.