Who Used Aid-in-Dying in 2017?

In the first year terminally ill Coloradans could legally end their lives with the assistance of a prescription drug, Colorado appears to be mirroring the experiences of other states where aid in dying is legal.

In 2017, most of the 69 prescriptions were written for people over the age of 55 struggling with cancer, heart disease or ALS, the degenerative neurological disorder. The vast majority of patients who died after seeking a prescription were white, under hospice care and residents of Front Range cities or suburbs.

Those trends closely track what initially happened in Washington and Oregon, the two states where aid in dying has been in place longest. Aid-in-dying is also legal in Vermont, California, Montana and Washington, D.C.

Colorado voters passed Proposition 106, which created the Colorado End-of-Life Options Act, in 2016 after several failed efforts to get a measure through the state’s legislature. The law allows a patient with six months or less to live to request and self-administer aid-in-dying medication. Physicians may prescribe the medication to patients who meet certain conditions and who are acting voluntarily. The law creates criminal penalties for coercing a patient to request the medication or tampering with a request.

Last week, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) released a report on the first year of aid in dying in Colorado.

In 2017, 69 Coloradans were prescribed medication they could use to end their lives. The CDPHE reports that 50 of the 69 Colorado patients filled their prescriptions and 56 of them died, some after taking the medication and some due to other causes.

Colorado does not track whether people who received prescriptions followed through and used the drug to end their lives. In Colorado, advocates argued that that level of data is invasive and that for some terminally ill patients, having the prescription or the medication can bring peace of mind even if they never use it. The cause of death in Colorado is listed as a person’s underlying condition, whether or not they took the lethal drug as prescribed.

Colorado in Context

Vermont, California, Washington, and Oregon all collect data about whether people take lethal doses after getting their prescriptions. Colorado does not. Oregon even tracks the time between the administration of a drug and death in some cases.

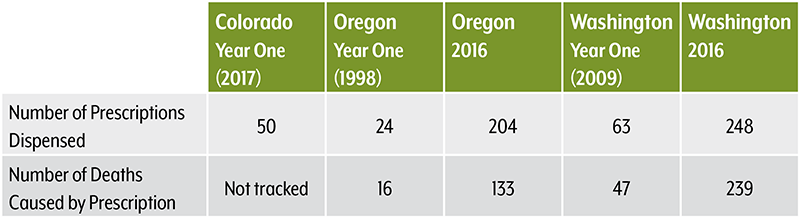

Despite the differences in what data is collected, a look at the numbers in Colorado compared with those in Washington and Oregon, where aid in dying has been legal longest, is still informative.

In Colorado, according to CDPHE, 44 of those who died after receiving a prescription had cancer, seven had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), seven had heart disease, six had chronic lower respiratory disease, and five had other illnesses or conditions. Cancer was the most common diagnosis in other aid-in-dying states. Heart disease and ALS were also common diagnoses.

Nearly all the Coloradans (96.4 percent) who died after seeking prescriptions were white. Some 88 percent lived in the Denver metro area or along the Front Range. Similarly, in Washington and Oregon, more than 90 percent of patients were white and most lived West of the Cascades, a region similar to Colorado’s Front Range. Even in more-diverse California, nearly 90 percent of those who died after seeking prescriptions were white.

Although other states have seen a disproportionately large share of college-educated people opt for aid-in-dying, that did not seem to be the case in Colorado last year. Nearly 40 percent of those who died after getting a prescription had a bachelor’s degree or higher, closely tracking the 39 percent in the state as a whole.

The experiences of Washington and Oregon suggest that Colorado is likely to see growth in the use of aid in dying as time passes. In both states, more people have used aid in dying over time.

Washington and Oregon also provide an insight into what might happen after people fill prescriptions. In both states, fewer people use the drug than fill prescriptions. In Washington’s first year, for instance, 63 people filled prescriptions and 47 of them died, 36 after ingesting the medication and seven without. The cause of death for the rest was unknown.

In Colorado, thirty-seven physicians wrote prescriptions in 2017 and 19 pharmacists filled a prescription. A representative for CDPHE told Colorado Public Radio that this suggests one of the fears of the aid in dying laws’ opponents had not come true: It appears that there are not physicians or pharmacists who have made a business of aid in dying.

Coming years will provide more insight into who is using aid in dying and why in Colorado.

For more on the debate over Aid in Dying, see CHI’s 2016 publication, Aid in Dying: Colorado Confronts a Difficult Policy Question.

Find CHI on Facebook and Twitter

Related Blogs

- Election 2016 Results

- Aid in Dying Movement Wins Early Legislative Victory

- “Aid in Dying” Bills set for showdown, Plus Our Weekly Bill Update

- Legislation in Review 2017

Related Research