Colorado’s annual rate of new HIV cases has dropped by a third in the past six years – no small feat. But this success is not shared by urban, suburban and rural areas alike.

Some less densely populated counties continue to struggle, with incidence rates declining much more slowly and in some cases even increasing, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC only reports HIV statistics for Colorado’s nine most populous counties because the number of new cases are not large enough in smaller counties.

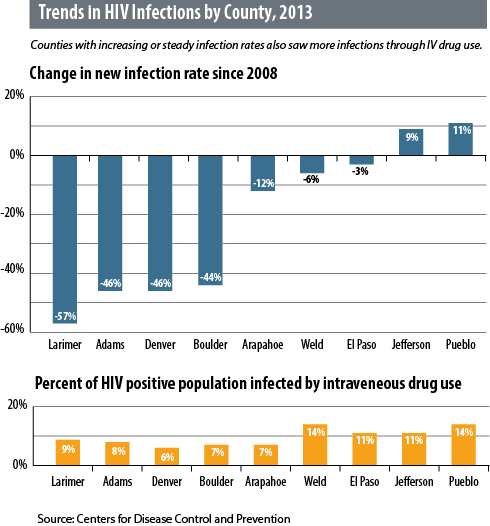

When examining a county’s success in addressing the HIV epidemic, it is important to note both the overall HIV incidence rate (the number of new cases per 100,000 residents in a year) and whether this is increasing or decreasing. Denver still has by far the highest rate of new cases. But trends over the past five years paint a different picture about the new realities of HIV. Larimer County, home to Fort Collins, has seen Colorado’s largest decline in the rate of new cases, falling 57 percent from 4.4 per 100,000 residents in 2008 to 1.9 in 2013. Adams, Denver and Boulder counties all have seen their rates drop by nearly half. However, the declines are small in Weld and El Paso counties. And the number of new cases has climbed by 9 percent over that time in Jefferson County and 11 percent in Pueblo County.

While poverty is often a predictor of health outcomes, it doesn’t seem to explain the differences in HIV infection trends among Colorado counties. HIV infection rates have fallen much faster in Denver, where nearly a fifth of the population lives under the federal poverty line, than in Jefferson and El Paso counties, where the poverty rates are much lower.

So what characteristics do the counties with higher infection rates share?

First, they are often severely medically underserved. Weld County, for example, has one full-time equivalent physician for every 2,511 residents, well above the benchmark panel size of one doctor for every 1,900 people that the Colorado Health Institute uses to analyze the adequacy of the health care workforce. The situation is even more worrisome in El Paso County, where the ratio is one physician per 2,917 residents.

Without access to care, people are less likely to know their HIV status and less likely to receive proper treatment if they are diagnosed, both of which increase the risk of transmission. Counties with high rates of incidence (new infections per year) are also more likely to have high rates prevalence (total people living with an HIV diagnosis), so knowledge of HIV positive status can be a powerful tool in helping to prevent new infections.

Second, these counties have less access to social services. Areas with needle exchange programs (Denver, Boulder and Larimer counties for example) have lower rates of HIV transmission through intravenous drug use. Other counties don’t offer such programs. El Paso County has an urban hub in Colorado Springs, but county officials have not approved a syringe exchange program. Transmissions from drug use are a significant part of the problem in counties with the most worrying trends in HIV infection rates.

The popular imagination often paints HIV as a primarily urban problem, and indeed rates are higher in metropolitan areas. However, we can’t forget about the unique needs of rural and suburban populations facing this epidemic. June 27 was national HIV testing day, and all of Colorado’s communities must be engaged in order to continue turning the tide against HIV/AIDS.