End Notes

1 “Data Brief 273 Tables: Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999-2015.” National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, February 2017.

2 Rose A. Rudd, MSPH; Puja Seth, PhD; Felicita David, MS; Lawrence Scholl, PhD. “Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths – United States, 2010-2015.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, December 16, 2016.

3 Holly Hedegaard, MD, Margaret Warner, PhD, and Arialdi M. Miniño, MPH. “Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2015.” National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, February 2017.

4 Heroin Response Work Group. “Heroin in Colorado: Preliminary Assessment.” April 2017.

5 “Poisoning deaths by selected categories: Colorado residents, 1999-2015.” Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

6 Christopher M. Jones, PharmD, MPH, Melinda Campopiano, MD, Grant Baldwin, PhD, MPH, and Elinore McCance-Katz, MD, PhD. “National and State Treatment Need and Capacity of Opioid Agonist Medication-Assisted Treatment.” American Journal of Public Health, June 11, 2015.

7 Lydia Aletraris, PhD, Mary Bond Edmond, PhD, and Paul M Roman, PhD. “Adoption of Injectable Naltrexone in U.S. Substance Use Disorder Treatment Programs.” Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, January 2015.

8 Nora D. Volkow, MD, Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH, Pamela S. Hyde, JD, and Stephen S. Cha, MD. “Medication-Assisted Therapies – Tackling the Opioid Overdose Epidemic.” New England Journal of Medicine, May 1, 2014.

9 Thomas F. Kresina and Robert Lubran. “Improving Public Health Through Access to and Utilization of Medication Assisted Treatment.” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, October 24, 2011.

10 “Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health.” Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016.

11 Wilson M. Compton, MD, MPE, Christopher M. Jones, PharmD, MPH, and Grant T. Baldwin, PhD, MPH. “Relationship Between Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use and Heroin Use.” New England Journal of Medicine, January 14, 2016.

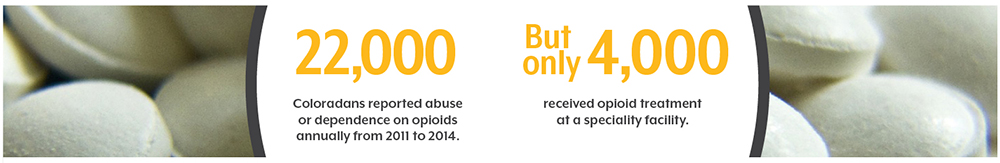

12 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2003- 2005, 2006-2008 (revised 3/12) and 2009-2010 (revised 3/12), 2011-2014.

13 Heroin Response Work Group. “Heroin in Colorado: Preliminary Assessment.” April 2017.

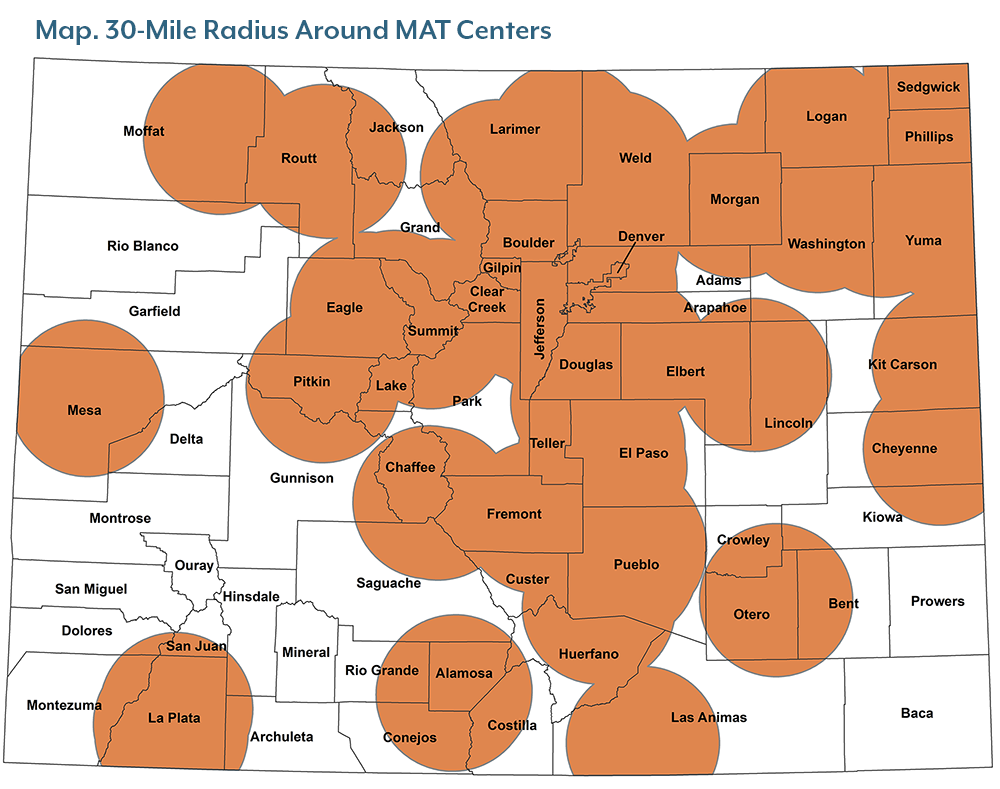

14 “Buprenorphine Treatment Physician Locator.” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed April 25, 2017.

15 “Safety Alert: Health Risks Associated with Exposure to Clandestinely Produced Fentanyl.” Drug Enforcement Administration, March 2015.

16 Nora D. Volkow, MD, Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH, Pamela S. Hyde, JD, and Stephanie S. Cha, MD. “Medication-Assisted Therapies – Tackling the Opioid Overdose Epidemic.” New England Journal of Medicine, May 1, 2014.

17 Christopher M. Jones, PharmD, MPH, Melinda Campopiano, MD, Grant Baldwin, PhD, MPH, and Elinore McCance-Katz, MD, PhD. “National and State Treatment Need and Capacity of Opioid Agonist Medication-Assisted Treatment.” American Journal of Public Health, June 11, 2015.

18 Alexander Y. Walley, MD, MSc, Julie K. Alperen, DrPH, Debbie M. Cheng, ScD, Michael Botticelli, Carolyn Castro-Donlan, Jeffrey H. Samet, MD, MA, MPH, and Daniel P. Alford, MD, MPH. “Office-Based Management of Opioid Dependence with Buprenorphine: Clinical Practices and Barriers.” Journal of Internal Medicine, September 2008.

19 Eliza Hutchinson, BA, Mary Catlin, BSN, MPH, C. Holly A. Andrilla, MS, Laura-Mae Baldwin, MD, MPH, and Roger A. Rosenblatt, MD, MPH, MFR. “Barriers to Primary Care Physicians Prescribing Buprenorphine.” Annals of Family Medicine, March 2014.

20 Roger A. Rosenblatt, MD, MPH, MFR, C. Holly A. Andrilla, MS, Mary Catlin, BSN, MPH, Eric H. Larson, PhD. “Geographic and Specialty Distribution of US Physicians Trained to Treat Opioid Use Disorder.” Annals of Family Medicine, January/February 2015.

21 “Continuing Progress on the Opioid Epidemic: The Role of the Affordable Care Act.” Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, January 11, 2017.

22 “Insurance and Payments.” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed April 4, 2017.

23 Nora D. Volkow, MD, Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH, Pamela S. Hyde, JD, and Stephen S. Cha, MD. “Medication-Assisted Therapies – Tackling the Opioid Overdose Epidemic.” New England Journal of Medicine, May 1, 2014.

24 Prevention and Chronic Care Program. “Primary Care Workforce Facts and Stats No. 3.” Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, January 2012.

25 “Trump Administration awards grants to states to combat opioid crisis.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. April 19, 2017.

26 “Increasing Access to Medication-Assisted Treatment of Opioid Abuse in Rural Primary Care Practices.” Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed April 3, 2017.

27 “Legislative Request For Interim Study Committee.” State of Colorado, April, 2017.

28 “Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention.”

29 “Colorado Plan to Reduce Prescription Drug Abuse.” Office of Governor John Hickenlooper, September 2013.

A version of this report with additional material is available in PDF form by clicking the link at the bottom of this page.