Steps Toward Improving Children’s Oral Health

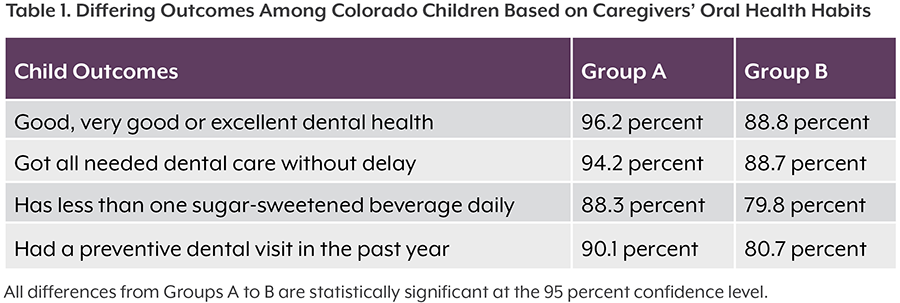

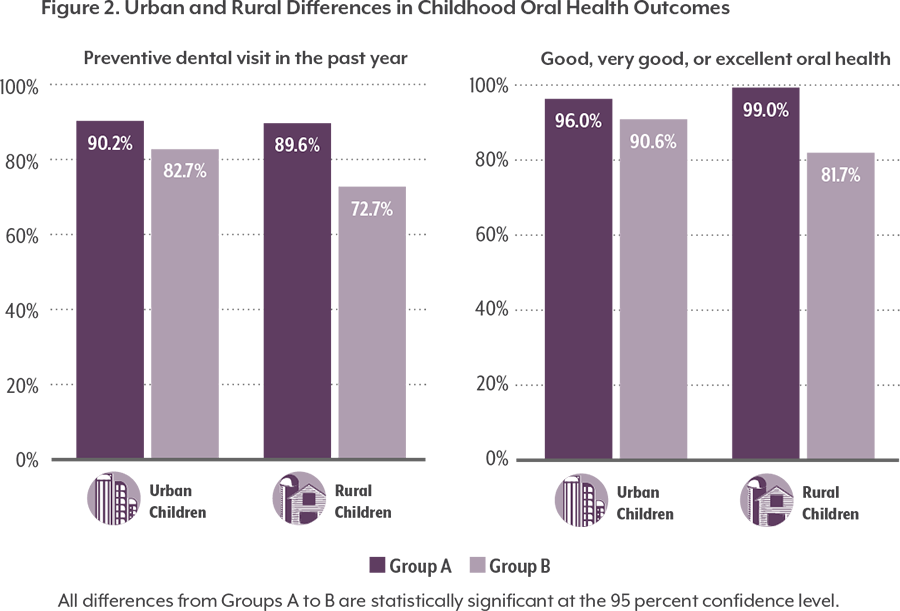

Children whose parents or caregivers receive dental care are more likely to get care themselves, especially preventive dental care. This may be especially true in rural areas. However, access to dental providers — a first step to improving oral health — is uneven across the state.

Of Colorado’s 64 counties, 57 are designated a Dental Health Professional Shortage Area by the U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration.5 Loan repayment programs for providers, including CDPHE’s Colorado Health Service Corps and its Dental Loan Repayment Program, encourage dentists and hygienists to work in underserved areas in an effort to help address existing workforce shortages.

Access to dental insurance is another important factor when it comes to seeking care.

An adult dental benefit in Medicaid introduced in 2014 provides greater access to care for low-income families. More than 90,000 parents and caregivers covered by Medicaid had a dental benefit in 2017. Medicaid’s dental benefit covers 19.3 percent of parents and caregivers in rural areas and 14.7 percent in urban areas.

Medicaid data show that enrollees are taking advantage of the adult dental benefit. More than 260,000 adult enrollees age 21 and over received dental care in the second quarter of 2016, according to the Department of Health Care Policy and Financing Dental Benefits Management Reports. This is a tenfold increase from the same time period in 2013 before the adult benefit was in place.

These data provide further evidence that expanding adult dental care leads to more children’s dental care. Nearly three-quarter of eligible enrollees up to age 21 (72 percent) received dental care in 2016, compared with 51 percent in 2013.

An upcoming change to payment models in Medicaid may answer key questions — whether medical providers can fill gaps in access to preventive care and whether there are adequate numbers of dental providers to care for Medicaid enrollees. Beginning in 2018, the Medicaid Regional Accountable Entities, an organization responsible for connecting Medicaid enrollees in a specified region with both primary care and behavioral health, will have a portion of their financial incentives determined by improvement on the number of enrollees with an annual dental visit.

Progress is being made already. The number of dental providers who rendered services for Medicaid enrollees grew by 78 percent, from 1,790 during the second quarter of 2013 to 3,180 during the second quarter of 2016.

However, children on Medicaid are less likely to see a dentist than those with commercial or private insurance. About three of four Medicaid enrollees younger than 19 (73.3 percent) saw a dentist in 2017, compared with 80.4 percent with private coverage.

Communities are working to expand access to care outside the dental office. School oral health programs, including school-based health centers, provide preventive services such as dental hygiene education, fluoride varnish and sealants.

Colorado’s Cavity Free At Three program trains medical and dental professionals to provide preventive oral health services for young children and pregnant women. The program also encourages dental providers to care for infants, toddlers and pregnant patients. Colorado adopted Medicaid policies allowing youth under age 21 to receive Cavity Free At Three services by making it possible for medical professionals to provide and bill for oral health preventive services. These preventive services, delivered in medical or community-based settings, have been shown to improve the oral health of children and decrease the need for costly dental treatment.6

Colorado is the second state in the nation with teledental programs and expanded scopes of practice for dental hygienists to allow for more dental care in communities that typically don’t have access to the traditional dental care system. Teledental services allow hygienists to prevent and manage oral diseases outside of a clinic setting. Co-locating hygienists in medical practices is also providing Colorado communities more opportunities to access care.