You’re Probably Getting Subsidized Health Care

It’s time for a quick health care budget quiz.

Can you name the federal government’s three biggest categories of health care spending?

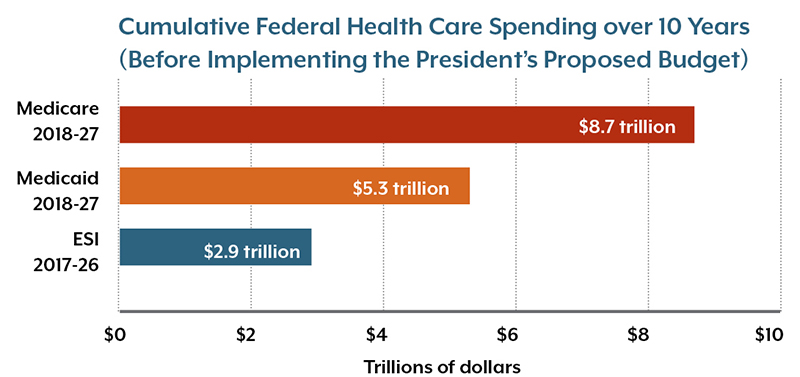

The first two are probably pretty easy: Medicare, the federal program that provides health care for senior citizens ($593 billion in 2017), and Medicaid, the program aimed at low-income and disabled people ($378 billion in 2017).

But the third category is not so obvious. It’s not Obamacare subsidies for people to buy individual coverage on the insurance exchanges ($50 billion) or health care for our veterans ($70 billion).

The third biggest category is the $222 billion tax exclusion for employer-sponsored insurance (ESI). Most Americans get their insurance through their employers, and the cost of the insurance premiums — whether paid by the employer or by the worker (or both) — is not counted like ordinary wages or salaries. The tax exclusion reduces workers’ income and payroll taxes. It’s essentially a subsidy for workers to buy coverage.

For many people, this answer comes as a bit of a surprise. The federal government’s health care spending doesn’t go to just senior citizens, the poor and disabled, veterans or those getting Obamacare subsidies. In fact, workers with ESI —and that’s 57 percent of Coloradans under the age of 65 and 56 percent of Americans in that age group — are receiving government help to buy health insurance.

The size of the tax subsidy is staggering. For context, the entire federal cost for the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act is around $60 billion, or about a quarter of the money that goes to subsidize ESI.

This graph shows total projected federal health care spending over 10 years. These amounts reflect baseline projections, without implementing President Trump’s proposed budget. One of the president’s major proposals, of course, is to cut the federal spending for Medicaid from $5.3 trillion to $4.7 trillion over the next 10 years, saving $610 billion in that decade.

Sources: President’s Proposed Budget, Fiscal Year 2018, Table S-3. US Department of Treasury. Tax Expenditures, 2018.

The ESI subsidy is an example of what policy wonks call a tax expenditure. The federal government doesn’t tax the cost of ESI premiums. This has two effects: less money goes into government coffers while people get the financial benefit of paying lower taxes.

In essence, the ESI subsidy acts like a government spending program, even though the government doesn’t literally send money to people to buy ESI.

Tax expenditures are somewhat hidden, as they do not ordinarily appear as line items in the federal budget. Other examples of tax expenditures include the deduction that taxpayers can claim for interest paid on home mortgages and for contributions made to charitable organizations. However, those two tax expenditures amount to about $119 billion a year combined — less than half the value of the ESI tax expenditure.

The ESI tax exclusion traces its history back to World War II, when the War Labor Board allowed employers to provide workers with tax-free benefits like health insurance, bypassing wartime wage controls. This is the historical basis for why America’s health insurance system today is largely structured around employer-based insurance – and why so much policy debate revolves around affordable insurance for those who don’t have access to ESI and need to obtain coverage through the individual market.

A discussion of the ESI tax exclusion is relevant to the budget and health reform debates going on in Washington, D.C.

First, is the $222 billion tax expenditure for ESI the best allocation of federal resources? On one hand, the ESI tax subsidy improves the affordability of health insurance for a lot of people. On the other hand, most of the benefits are concentrated among higher-income workers, whose wages would be taxed at a higher rate.

Second, as the president and Congress hash out a budget that controls the deficit, Medicaid is the primary target for spending reductions. In most discussions, Medicare is largely untouched, and changes to the ESI tax exclusion are politically unpopular. So, the health-related question is this: Will large reductions in Medicaid spending have greater adverse impacts on overall health than modest reductions in spending for Medicare or the ESI subsidy?

Medicaid is probably an easier target for budget cuts because its political constituency is less powerful, but one has to wonder whether it’s sensible — from health and economic perspectives — for Medicaid to bear most of the brunt of the budget axe.